Authorial-Leverage-Framework

Jacob Garbe's PhD Dissertation on increasing authorability for dynamic/generative narrative systems

Project maintained by Logodaedalus Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

The Authorial Leverage Framework

Introduction

Hey, I’m Jacob! I’m a technical narrative designer. I co-created Ice-Bound, an award-winning indie narrative game, and have developed dynamic narrative systems for a variety of industry studios over the last seven years. This article distills the framework I created while researching authoring for narrative systems for my PhD, and later refined during my journey in industry. It’s about how to manage scope when creating dynamic narrative systems for games. Specifically, it centers on increasing authorial leverage—or how easily content can be created—for dynamic narrative games.

Originally I wrote this just for narrative designers and writers, but it’s meant to be used holistically by engineers and producers as well, because many of these considerations cut across disciplines and departments, even though they mainly concern narrative content. I tried to simplify everything down as much as possible to make it (hopefully) approachable. If you want to read a more expanded and detailed breakdown, you can check out my dissertation.

So first off, when I say “dynamic narrative games” I’m painting with a really broad brush. For me, it can mean many things: games driven by deeply reactive character dialogue, system-driven games whose narrative is closely tied to game mechanics, open world games whose narrative deeply responds to player actions / game state, and much more! I’m not interested in strict definitions or minting new terms, just proposing a useful framework for people working in similar spaces.

Creating content for dynamic narratives, compared to static ones, comes with some design challenges that often make shipping games with them difficult or infeasible. Many times the task of solving these problems falls on narrative designers and writers. And when they can’t move mountains, things get cut. But if narrative designers and writers can figure out how to characterize and design dynamic narratives while accounting for these challenges, then we can (hopefully) make these types of games more feasible, and thus more likely to ship.

That’s what this framework is for! I created it by generalizing lessons I learned from both industry and my own personal projects. If you want to know more project specifics, you can check out my write-up on Ice-Bound, StoryAssembler, and Delve. But for now, we can gloss over it and say that each one had its own particular challenges, which came from each project tackling dynamic narrative in different ways. For some I successfully navigated the authoring process, and some it proved more…difficult.

This isn’t a restrictive manifesto, just my own way of looking at things given those experiences. Take it or leave it, in part or whole, but my hope is that it’s useful to you!

Why Dynamic Narrative Systems, Anyway?

As games have gotten more complex over the years, players have come to expect more from their stories, especially when narrative is a central pillar. Because of that, there’s a push to create more dynamic and reactive narratives, requiring more sophisticated systems to tell them. Creators, both AAA and indie, turn to dynamic narrative systems to offer experiences that are more reactive to player actions and emergent game state, and thus more unique and compelling.

Well-formed dynamic narrative systems take work from the get-go. They’re not something lightly slapped on at the end of a project. Specifically, game designers employ them for very specific reasons. They may want players to experience a sense of agency and control through making choices at key narrative points, as in Telltale games. Maybe they want players to experience a feeling of agency, but through affecting the gameplay system (which in turn affects the narrative), like in King of Dragon Pass / Six Ages. Or maybe the dynamism of the narrative system isn’t necessarily the focus, but rather an emergent requirement from the narrative needing to support reactive and dynamic gameplay, like Bethesda’s “Radiant AI / Story” system, or context-triggered vignettes and quests in Hades or Horizon Zero Dawn.

What Are Their Production Problems?

Those games are so great! Why don’t we see more of this stuff, anyway?

First off, it’s not a tech or engineering challenge. There’s a temptation when looking at complex dynamic narrative systems to assume they also must require intense engineering. I maintain that most engineering required by dynamic narrative systems has been around since the 80s. Most tech in even the best cutting-edge dynamic narrative games looks simple on paper, if you’re looking purely at implementation and what engineers are being asked to support.

Maybe that’s provocative, but I say it because I think engineers can feel intimidated when taking the same code you’d use for a behavior tree or NPC pathing, but apply it to more abstract and high-brow things like “relationship graphs” and “narrative tension”. Because most engineers aren’t familiar with fundamentals of narrative design and writing, and most narrative designers and writers aren’t familiar with the fundamentals of engineering, there’s lots of cross-talk and confusion in representing their ideas to each other, and lots of thinking the other person is doing impossibly complex things, instead of relatively simple but very specialized things. One of my favorite parts about being a technical narrative designer is bridging those gaps! You’d be surprised how far you can get with just a graph data structure and tagging. All three of my personal projects, which in both form and function were wildly different and very complex, at their heart were graph data structures with tagging, and different approaches to traversing them. It’s a rich territory to explore!

So if the challenge isn’t engineering, then what is it? I maintain it’s both a design and production challenge. I’m not a producer, so I’m going to focus primarily on the design side of things.

First off, even if you do everything right, writing content for these systems is a lot of work! And if you’re not smart with your design, it gets worse very quickly. Generally there’s two ways things get worse. First: the more dynamic the narrative, the more expansive the player interactivity, and the more content required to surface that. Scope creep is always a problem when designing games, but scope creep with dynamic narrative systems can balloon the content requirements for your game incredibly fast. Second: if you don’t account for the dynamism / interactivity when designing and engineering your narrative system and its pipeline, creating cool dynamic content can easily become more work than just writing static content to cover all your bases.

Put another way: writing challenges for these games are about both quality and quantity. And these problems can bite you from many angles. For example, sometimes even if dynamic content is created to broadly cover more interactions, and is reusable in different situations (so you need less of it overall), it creates a different problem: authoring complexity. Authoring that kind of dynamic content–even highly-reusable content–can be so complex, it slows production down until the game’s narrative could have been written faster using simpler, static methods, even though the volume of content needed would be much higher.

Systems where writing a huge amount of static content is faster than taking time to write smaller amounts of dynamic content, are being blocked by the “authoring wall”. If you don’t overcome this, you’re in trouble!

The Authoring Wall

The authoring wall [1] is the effort required (for writing or otherwise) to achieve higher levels of dynamic narrative. The general idea is that static authoring gives you reliable incremental progress, but with no compounding effects. It’s easy to scope out, and reliable for hitting project checkpoints, but will never move things along faster than linear progress.

Dynamic authoring, on the other hand, may not initially get you as much progress as static authoring, but is constantly compounding. Therefore, at a certain point in production, you start getting way more out of the system than could be achieved with static authoring.

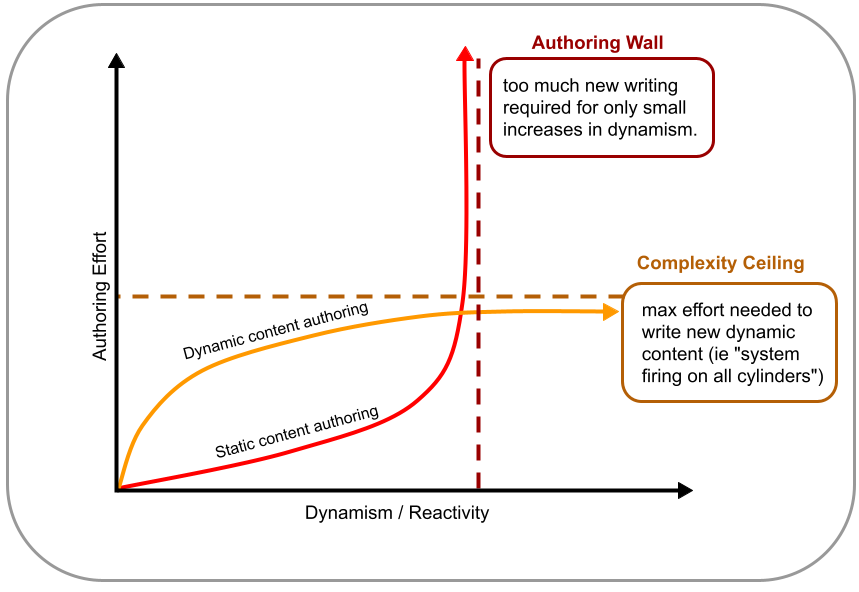

If a visual helps, here’s two graphs I like to use to illustrate this.

Graph modified from Mateas et al.

This first one shows authoring effort versus dynamism / reactivity. The idea is that for games, the more dynamism / reactivity you put in it, the more writing you have to do. The requirements compound, but the progress you make with static authoring doesn’t. So as you push further into this territory, your writing starts to balloon. Imagine this like an open world game with NPCs. Increasing the dynamism by adding new static conversation trees to talk about pets to different NPCs compounds across all NPCs, which starts exploding the writing requirements to cover that.

In contrast, dynamic content authoring might take longer to initially set up systems and content to feed different cases within those systems, but later on if you want to add new conversation topics to NPCs, instead you can repurpose or modify existing content to accommodate that, instead of having to write new material whole cloth. Ideally though, the complexity of creating content for your system tapers off and doesn’t get more and more complicated, which would pose a problem on its own! I call that the Complexity Ceiling.

So given that, we say static authoring hits the Authoring Wall when confronted with too much dynamism in the game, and dynamic authoring can shoot past that, as long as creating content in that system stays below the Complexity Ceiling.

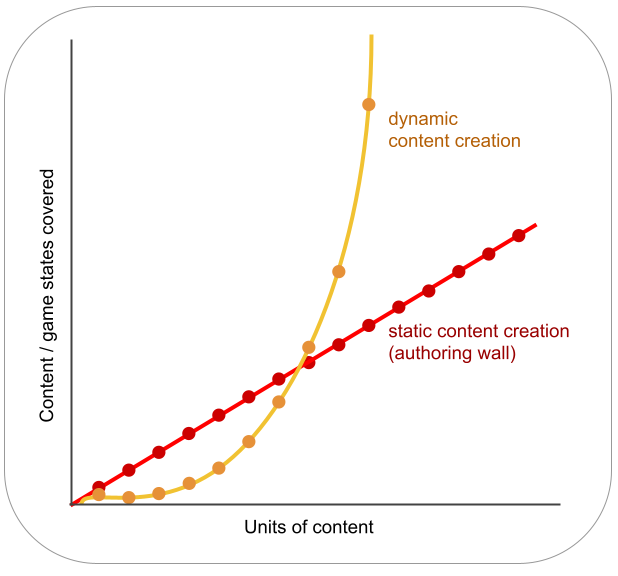

Another way to say the same thing, but with more of a production lens, is looking at “covered game state” versus “units of content”.

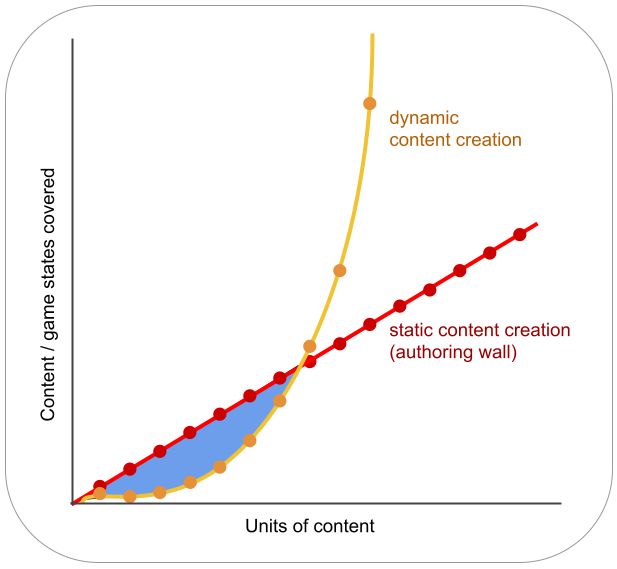

Focusing on dynamic content creation, we could alternatively say the authoring wall is the amount of progress you’d make from static content creation (whatever that is for your game). Again, static authoring always makes incremental progress for each piece of content added, but never gets “bonus” coverage due to compounded things from the dynamic system. So if your dynamic content system isn’t doing better than that, you’re putting in a lot of work for nothing!

That’s not to say it should be blowing static methods out of the water from the get-go! Most of the time you’ve got to put in more work to give the system enough stuff to chew on, before you start seeing the benefits. For example, say you’re writing tag-driven conversations. Compared to just writing a bunch of regular conversations, it might take you longer to write lots of different things characters might say in different circumstances, given different tags. And there’d probably be some wonky stuff in there to tell the system when and how to use it. But once you pass the inflection point where you’re getting good results, now all the content you’re writing can hit multiple conversations, boosting the states covered in your game in multiple ways. If you want to increase the number of characters you talk to in a game from 100 to 10,000, that may not even be achievable with static writing, whereas the more dynamic system-driven approach may be able to handle it just fine (given some design factors we’ll talk about later).

That’s what this graph is attempting to show. Even if it’s slower at the beginning, you want to get to the point where your dynamic content is more efficient at covering your bases than static content as quickly as possible. And even if it takes longer to write dynamic content (for a variety of factors we’ll get into) if it gets reused dynamically in different contexts enough times (i.e. covering more game states) it’s “faster” than static content. For example, if you’re writing a brief greeting conversation between NPCs with a dynamic system, it may take 10x the time to just write a regular version of it, because you’re adding tags to different parts of it, or conditional logic, or using some funky custom tool your engineers made. But if that piece of content gets used even just 11x more than a static one, it’s still time better spent.

That concept, of how content compounds, is called authorial leverage [2]. You want to increase authorial leverage, so that your writers can hit the ambitious targets of your game. This framework will hopefully help you do that, which is why I call it the Authorial Leverage Framework.

In general, there are two ways teams get in trouble. One: if you’re in the blue area of the graph for too much of production, and the system never “fires on all cylinders”, producers are often tempted to cut back procedural content wholesale to ship with the content you have, not realizing that the more you cut off the end of the curved line, you’re actually maximizing the damage your cuts are doing to your content. Two: when the gains you get from dynamic systems (how steep the curve goes) are too low for the production or technical / QA headaches they introduce to justify their existence, you again often end up cutting them back to ship.

If all this seems like a lot, don’t worry! These are the dynamics we’ll be breaking down in the framework itself. Long story short, you’re only past the authoring wall if making a piece of dynamic content is either faster, or covers more cases than the time it would take to do it the static way.

Why Are You Talking So Much About Scope?

Whichever way you look at it, overcoming the authoring wall requires careful planning and design. And because of this, you should make sure you actually need dynamic narrative content, because it’s an engineering and authoring commitment, and a lot of work. Many times if you really look at your design, it can be satisfied with static content more reliably, as long as you’re ok with writing lots of it.

However, for some designs, you definitely need dynamic narrative systems and content to achieve your design goals. And by leaning into the strengths of your systems, you’ll create more useful content than what you’d get from just writing static content. Also, as a general design rule, showing the system’s full power to the player through good content design creates a unique feeling that can both help guide the player’s interactions by showing the types of play the system’s good at, and better communicate the story it’s trying to tell.

For projects looking to keep to a deadline or guard against scope creep, understanding the project’s authoring wall is a critical part of the design process early on, so you can decide how dynamic you want to go, if at all. And critically, where you hit the authoring wall isn’t just a technical system question your engineers can answer! It depends heavily on your narrative design.

Generally, if the narrative design of the experience leans into system strengths, you can get past the authoring wall faster, because you’re more effectively covering the game’s space (by tailoring it more to your system). But on the other hand, the more dynamic the system and design, in general the further out the wall will be initially (requiring more authoring up front). The hope is that despite that, the leverage is even greater once you’re past the wall, and thus it’s worth the extra effort. A good design can curve your dynamic content line so you shoot past the wall quickly. A bad design can flatten your curve or worse. A good rule of thumb for designing these systems is making sure the required static version of the same content balloons way out of scope quickly, because that means the dynamisms of your system are being exploited to create a unique experience. If you can look at what you have at a given point in production, and can’t even imagine how much static writing it would take to get the same effect, that’s a good place to be in. But if writing static content is still comparable to your dynamic content far into production, that’s a big red flag that you need to adjust your design!

I’m using lots of production talk because the emphasis for this framework is to help you push dynamism as much as possible that’s also shippable on a deadline. There are many amazing narrative systems out there in academia, for example, that are useful from a research angle without creating finished games / experiences. But in industry, when designing systems for a game that needs to ship, you definitely don’t want to end up with an amazing dynamic narrative system, but no time to finish actually writing your content.

And again, this framework comes from spending around seven years implementing dynamic narrative systems and games with them, both in academia and industry. Hopefully it helps you think about your narrative design and authoring tools in such a way that you can get past this authoring wall as quickly and painlessly as possible, while pushing the boundaries of dynamic narrative games!

The Authorial Leverage Framework

Every game is different, but in general, to tackle the unique design challenge each one poses, we need to understand two things:

- how much content we’re talking about (Traversability)

- how hard it is to make it (Authorability)

This framework’s all about asking ourselves tough questions. Traversability’s question is pretty straightforward: how much of the authored content is seen by the player by the time they’ve completed their playthrough? What you use as “completed their playthrough” can be as specific or ambiguous as is useful. But the key components of it, regardless of whether you’re focused on a casual player that won’t ever complete more than 10% of your story, or supporting die-hard fans that platinum the whole thing, are

- Explorability: how much content does the player see in a complete playthrough?

- Replayability: how many times is the player replaying the same content?

- Reusability: how often could you reuse content in different contexts in a playthrough? How many different prospective playthroughs could content reappear in?

- Contextuality: how reactive / dependent is the content to player interaction / game state, and how large is that state space? How granular?

The answers to these Traversability questions determine the scale of what we’re asking our writers and narrative designers to do. If you want to get more detail on this, I talk about it more in this dissertation section.

Authorability’s question is: how difficult is it to write content for your game? Your system might need lots of content, but if you can make it fast, that might be fine! And authoring tools can help you make content faster. Obviously the more polished an authoring tool is, the better. Ideally you’d have a perfect tool that magically enables peak creativity and productivity, but realistically that’s not the case.

Most dynamic narrative systems are game-specific custom implementations, so the editors / tools are usually rough and focus more on bare functionality than polished UX. Many times these systems use a custom language or syntax that requires deep on-boarding for new people, even if they’re veteran writers. And even if your syntax isn’t custom, usually the narrative conventions are project-specific! For example, you might use Ink, but with bindings to custom external functions in Unity, and have specific authoring conventions around when it’s appropriate to update state, or the design of story branches offered to the player within a scene at particular times.

And even more generally, places like Choice of Games or Telltale have a “house style” that many times are welded to the tools they use. Because the systems in many dynamic narrative games are bespoke or one-off, it also means the “house style” evolves over the course of production, and only lasts on a per-project basis.

So given that, let’s break down the general authoring challenges for these types of systems into two pairs of questions. The first pair concerns the mechanical art of writing:

- Proficiency: what data format are authors required to work in? How technically demanding is that format?

- Complexity: how many different components does authoring a single piece of content entail?

The second pair of challenges concerns the conceptual art of writing:

- Clarity: how complex are the state/system dynamics that need to be kept in mind while authoring?

- Controllability: How difficult is it to create content that’s shown to the player when you want?

A quick note on Controllability: we’re specifically asking how easy is it to avoid creating something with bad dynamics, or dynamics that create unexpected bad output. As a general rule, we always desire high Controllability, though what is “high” or “low” differs from game to game. If your game has lower Contextuality (from the Traversability side of things), like a series of vignettes or “bottle episodes”, then you can get away with less Controllability, because they each can stand more or less on their own. But if you’re doing things with persistent or reactive context, like content that shows up in response to sequences of specific player actions over time, then Controllability is a bigger deal!

The answers to these Authorability questions determine the difficulty of what we’re asking our writers and narrative designers to do. If you want more detail on this part, I expand on it in this dissertation section.

How Do I Know I’m In Trouble?

That’s great as an abstract thing, but what are “good” answers to those questions? How do we know we’re in trouble? For each of these qualities, they have desired values of Low or High. Here are some examples of bad situations to help illustrate:

- High Proficiency: writers have to write in a text editor using a custom JSON data format you’re parsing into the engine, submit scripts into a version control system like Git or Perforce, and run build processes to see their content in-game

- Why is that bad?

You’re not only decreasing your pool of talent by requiring technical skills, you’re pulling them out of creative space by forcing them to engage the “technical side of their brain” as part of the creative process.

- Why is that bad?

- High Complexity: in order to author a piece of content you need writers to create three different pieces of content in different formats and different files, synchronized by a unique id, each with different authoring requirements.

- Why is that bad?

Requiring lots of context switching makes it difficult to get into a flow state while being creative, and you introduce more failure points where formatting errors can force writers into a debugging role instead of managing the content they’re creating.

- Why is that bad?

- Low Clarity: writers have to write character vignettes that may show up in a variety of different circumstances, but still need to accomplish very specific dramatic goals, and they have to track that manually, or maybe it’s unclear where the vignettes will show up contextually.

- Why is that bad?

Requiring writers to manually track this means they end up doing more context checking than actual writing, which slows production and can lead to content that has to be thrown away or re-done because it doesn’t fit.

- Why is that bad?

- Low Controllability: writers have no way to test when content shows up, or the methods of controlling where it shows up are too unreliable to consistently use.

- Why is that bad?

Because writers don’t have a good way to test how content appears, or the system showing it is too unpredictable, or production demands emergent narrative always conforms to rigid guidelines, writers spend more time trying to find the “correct” spot to write in, than actually writing in it!

- Why is that bad?

In a lot of projects, the failure state of dynamic content is static content. So in many of these situations, there’s a risk that writers end up only writing content in a static manner within a dynamic system, either because there aren’t adequate QA tools to reassure production or stakeholders that unexpected things won’t happen, or making content is so complex they have to stick to simple patterns in order to understand what the system’s doing. Either way, you end up wasting engineering supporting a dynamic system that only actually has stakeholder buy-in for static content, or the ability of your writers to create effectively static content with it!

So the key takeaway is that if Authorability in your project is low, even small-scale narratives can have trouble shipping. For example, even if you only have to write fifty pieces of content to ship, if doing that involves a nightmare pipeline with a hundred different separate things that all have to be precisely configured or nothing works, and it’s hard to prove it always works, then that project is in more danger than one requiring five hundred pieces of content that can get done quickly and are easier to control and approve.

So How Do I Fix This?

Well great, so according to this metric your project’s in trouble. How do you fix this? You can either try to lower Traversability, or increase Authorability.

Reducing Traversability is essentially cutting scope, which is familiar territory to anyone in game dev. The general vibe is trying to reduce the amount of game state you need to cover, and reduce the complexity of content needed to do that (which is usually where Replayability, Reusability, and Contextuality come in on the authoring side). If you don’t mind repetitive content because you’re making a cool Roguelike game, then fine! Use whichever version makes your life easier. You know which one it is. It’s the one you don’t want to do.

- Lowering Explorability

Reduce the raw scope of the experience, the amount of different things the player sees in a playthrough. - Lowering Replayability

If you wanted to provide different outcomes in different playthroughs, whittle down and focus on first providing a good initial playthrough. - Lowering Reusability

If it’s too difficult to make content systemic enough it can be reused in lots of places, cut down on that! Remember, if it takes longer to write content reused in three places than just writing three pieces of regular content, you’re in trouble! - Lowering Contextuality

Stop trying to represent so many narrative things contextually to your system, and instead lean into the reader’s apophenia to read patterns into things that aren’t there. With skillful design and writing you can get further than you may think!

It broke my heart to even write that advice. So the other side of the coin is to keep your Explorability where it’s at, but you need to increase Authorability ASAP! You can do that by:

- Lowering required Proficiency

Don’t make your writers learn highly-technical tools / syntax. Try to keep authoring as intuitive and low-tech as possible, or commit more to custom tooling so writers can focus on what they’re good at: writing. - Lowering authoring Complexity

Reduce how many different steps it takes to make a thing, and automate as much as possible. Cut down on repetitive data entry, and maximize the time your writers spend writing! - Increasing authorial Clarity

Give writers a way to see how the thing they’re writing will affect the game overall while they’re writing it. Don’t make them guess. - Adjust Controllability

You can either decrease or increase it, given your preference. Either make peace with chaos, or ratchet up constraints and give the appropriate tools to track that. But make sure everyone’s on board with appropriate expectations! If increasing Controllability however, beware you aren’t actually painting yourself back into a corner where static content would do the job just as well.

So in general, you want to increase Authorability through authoring tools, or streamlining your content creation pipeline through automation, which enables more content to be produced. That way, even games with high Traversability that demand lots of authoring can still be achievable.

Applying The Framework

Instead of waiting until you’re in trouble, you can also try applying this framework at various project stages to inform decisions you make as you move from prototyping through production, and the last push before shipping.

Pre-production

- First determine the type of experience you’re trying to enable. Your gameplay and experience pillars. Those are your north stars. You already did that, right?

- even if the systemic work you’re doing is abstract and engineer-y, use the experience design as a lens to focus your development efforts on concrete system deliverables. How are players making choices? How is the game responding to them? How fluent are those responses? Get specific! Come up with concrete user stories and exemplar content, to reveal how the system should generate more!

- Now take those pillars and set them down in terms of Explorability, Replayability, Reusability, and Contextuality

- Think about which ones are most critical to exhibit the strengths of the total system (the “system pillars”)

- Use that to triage features to cut, or “dial down” the generativity of some systems (or make them static) in order to combat runaway authoring requirements

- Plan out your content production pipeline, and make exemplar content. Authorial burden can crop up not just in writing, but tools and processes it takes to translate that into your game. It can also help tease out which content your system is best at, and therefore what kinds of content you should prioritise for authoring

One of the most important things coming out of pre-production on dynamic narrative games is having a clear sense of Traversability and Authorability. You want to know roughly how much content you’re going to need to ship, and have a rough sense of what the authoring experience is going to be for that. Inevitably going from prototypes to the real thing involves cutting back on generativity in some way, so you want to be well-positioned to make sure those cuts are as effective as possible, without hurting the core pillars of the game.

Production

Every dynamic narrative system has authoring patterns or templates. These patterns may have generalizable attributes cross-system or between families of systems, but usually they’re specific to the project’s architecture and experience design. Recognizing and codifying these patterns can increase Clarity, because once you develop them as templates, you don’t have to do that initial cognitive work again. So as content creation begins,

- identify content dynamics that repeatedly make good content

- codify / parameterize them through narrative design

- make it easy to re-deploy them through authoring guidelines or bespoke templates

- Get specific! What kinds of choice dilemmas are juicy? What kinds of context-triggered vignettes spark joy? What is a pattern that will still delight the player even if it’s the fiftieth time they’ve seen it under different circumstances?

Late production (when it’s time to cut)

All dynamic narrative systems have a baseline of complexity. That complexity allows a specific set of expressive affordances. So far I’ve been talking as if all a game’s narrative content is monolithic and homogenous, but in practice that’s never the case! You can tweak specific parts of your narrative to showcase the system, then dial it back. So when looking for things to cut,

- Push Complexity high only in controlled, specific cases the player will remember

- Lower the Complexity in other specific instances to reduce the difficulty or scope of content you need to ship

- Leverage the general concept of “hero” content for your system

- build more dynamism into “hero moments” that showcase your system’s complexity

- turn the knob back down to more manageable levels before and after, and players will assume you’re still doing complex things

- as long as the player can retain a sense of agency by thinking the game is reactive or responding to them, you can cut back selectively to static content (especially if the content is compelling narratively, not just expressively / mechanically)

- Like a witness tree left after a clearcut, even if you can’t support the full system across the entire experience, at least you can still give players some unique moments.

No matter what, don’t lose sight of why you wanted to do dynamic narrative in the first place! Cut back to hero moments or lower levels of dynamism, but unless the project is in absolutely dire straits, resist the urge to wholesale cut what makes it unique and dynamic in favor of “tried and true” techniques that also risk making it forgettable. Again, having a solid production plan and making sure stakeholders are as on board as possible can help defuse these problems before (hopefully) they become problems.

Wrap Up

That’s it!

Well, not really. If you wanted to read more, I suggest the Introduction and Conclusion of my dissertation. If you’re thirsting for another 320 pages about it and the narrative systems I developed that led me to this framework, along with some juicy related work of historical interest, read the rest! Hopefully this framework can be useful to you as you make your way through the jungle of planning, creating, and finishing a dynamic narrative game. There are so many interesting stories to tell, and so many intriguing ways to tell them! Again, the main challenge I see facing creators of dynamic narrative games isn’t engineering of systems to tell their stories, but the design and production “technologies” needed to effectively create a plan and see it through. This framework is hopefully one such technology. May it point the way for you to even greater things!

Notes

[1] Michael Mateas, Elizabeth Andre, Ruth Aylett, Mirjam P. Eladhari, Richard Evans, Ana Paiva, Mike Preuss, and Michael Young. Artificial and Computational Intelligence in Games (Dagstuhl Seminar 12191). In Dagstuhl Reports, Volume 2. Schloss Dagstuhl-Leibniz-Zentrum fuer Informatik, 2012. Link

[2] Authorial leverage was first formally defined by Chen et al as “the power a tool gives an author to define a quality interactive experience in line with their goals, relative to the tool’s authorial complexity”, although previously used by Strong to talk about combinatoric authoring, and simply as “leverage” by Mateas when discussing semiotic systems that facilitate authoring for complex systems.

- Sherol Chen, Mark J Nelson, Anne Sullivan, and Michael Mateas. Evaluating the Authorial Leverage of Drama Management. In AAAI Spring Symposium: Intelligent Narrative Technologies II, pages 20-23, 2009. Link

- Christina R Strong and Michael Mateas. Talking with NPCs: Towards Dynamic Generation of Discourse Structures. In AIIDE, 2008. Link

- Michael Mateas. Expressive AI: A Semiotic Analysis of Machinic Affordances. In 3rd Conference on Computational Semiotics for Games and New Media, page 58, 2003. Link